‘This cape is a most stately thing and the fairest cape we saw in the whole circumference of the earth.’

Sir Francis Drake (or the ship’s chaplain) upon seeing the Cape Point on his circumnavigation of the world on the Golden Hind (1580)

Another way around

By 1450, the days of the old Spice Route of Marco Polo’s fame, from Asia to Europe, were closing and throttled by the mighty Ottoman Empire which, by this stage, controlled the eastern Mediterranean. The European traders were suffering, Europe’s wealth was suffering and the only answer to this impasse was to find another route to the East. There were two options, go West into the unknown and hopefully reach the East or find a route around Africa.

The ramifications of this forced decision changed the world forever. The European maritime powers, in their quest to find another route to the Far East, discovered other lands, established trading stations, started settlements and, finally, colonised these new lands. The question needs to be asked, what if the Ottoman Empire had kept the Silk and Spice Route open for Europe? The world today would be a different place, The Americas and Africa would have a different history, the western slave trade might not have happened as we know it and some countries would not have been colonised.

Africa had seen sailors from Europe, the Middle East and India slowly creeping down its coastline on both sides of the continent, on ever longer reaching journeys towards the unknown tip of Africa. These sailors understood the fact that the world was round and, therefore, Africa had to have an end point somewhere. There were stories about the Phoenicians rounding the tip of Africa over 2000 years ago. The Greek navigator, Eudoxus of Cyzicus, in 130 BC was also, supposedly, a contender or died on his quest. A planisphere (map) known as the ‘Semito’ illustrated in 1306, mentions what seems to be the Cape Point; the ‘Fra Mauro’ map of 1450 mentions the southernmost point of Africa as ‘Cape of Diab’ (basing this information on a 1420 expedition undertaken from India). Lately, there has been a push for Zheng He, the famous Chinese navigator, as the first to have circumnavigated the world in 1421-1423, making him also a potential contender for first rounding Cape Point. All these stories have been tested but, due to lack of evidence, improbablities and lack of proof, historians will stick with the accepted narrative we have today until enough evidence dictates otherwise.

The first visitor missed it by miles

By 1400, the Portuguese had crossed the equator. 1485 saw Diego Cao reach modern day Namibia and, by January 1488, Bartolomeu Dias the Portuguese navigator, was poised to be the first foreign visitor to Cape Point. The renowned Cape weather rained on his parade by sending a violent storm which blew his ships out of sight of land and into the beyond. Days later, he decided to sail east and then north where he stepped ashore at Mossel Bay, a few hundred kilometres up the east coast. His journey to the East was stopped near Port Elizabeth when his crew advised him to turn back in a mutinous tone. It was only then, on his return journey in May, that, for the first time, he saw Cape Point in all its glory. It must have been fine weather for him to put in at Dias or Maclear Beach to erected his Pachao De Sao Filipe ‘Stone Cross’ on Cape Maclear to claim this newfound place for his King (Christian marker to claim territory and to be used by future sailors as a positioning beacon). Dias named Cape Point, ‘Cape of Storms” and later re-named it ‘Cape of Good Hope’ - there is a school of thought that Dias put in at Buffels Bay on the False Bay side of the Point where he erected his Pachao De Sao Filipe but, to this day, no evidence from both sites have yielded proof. Dias had unlocked the door to this new route to the Far East but it was Vasco da Gama in 1497 who completed the full journey, a journey that would make Europe rich and make it a dominant power in the world for the next 400 years.

What had Bartolomeu Dias discovered at Cape Point?

As well as the key to the Far East, he also discovered an extremely old peninsula made up of solid rocks which started forming 560 million years ago in an ancient sea. With millions of years of sediment build up, through periods when the sea was deep and periods where it was considered a river or a tidal mud flat, these deposits buried under immense heat and pressure, formed into rock (at one stage, Table Mountain and the Cape Peninsula range being more then twice the height that they are today, before erosion took its toll). Around the 540 million year mark, molten magma from deep within the crust mantle, slowly rose up while cooling. This hot magma managed to intrude the bed’s oldest rocks, deep-marine siltstones of the Malmesbury Group, that makes up the basement of the peninsula.. This granite now makes up virtually all of the base rock of the Cape Peninsula except for Cape Town (City Bowl and Sea Point) which still has the original base formation of silt stone. By the time that these formations were exposed through erosion and uplifting, they had all become solid rock.

One of the biggest geological episodes that helped expose these rocks, and started the erosion process, was the forming of the Supercontinent Gondwana, when South America and the Falkland Plateau crashed into southern Africa in slow motion about 300 million years ago, moving at a rate of two centimetres a year over millions of years. The force was so great that they managed to buckle, bend, contort, twist and fracture these once horizontal formations which, in some places, left the bedding planes in beyond vertical positions. Table Mountain, and the chain of mountains running all the way down the peninsula to Cape Point, was fortunate to escape most of these distortions. This happened because, as the lateral pressure built up and the rock formations started to buckle, forming arch-like anticlines and U-shaped synclines ridges and valleys, Table Mountain and the peninsula range, found itself right in the centre of a syncline valley, exposing this area to the least amount of buckling. Is it not ironic that one of the oldest mountains in the world was once a valley?

After this period, millions of years of natural erosion has helped shape and slowly reduce this mountain range in size. This erosion took an extremely long time, considering that this mountain range has one of the slowest erosion rates in the world, at 2-7 mm per 1000 years and is also considerd one of the strongest mountains in the world because it is virtually 100% pure quartzite.

The fact that this area is made up of nearly all quartzite which is extremely nutrient-poor for plant life, brings us to the next thing that Dias must have seen and walked through but not realised the significance, that he was the first foreigner to discover the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest, but richest in species per unit area in the world’s six floral kingdoms, with over 9000 species, of which two thirds are endemic. Most of this floral kingdom is made up of fynbos (fine-leaved plants) which have specially evolved to flourish under the Cape’s harsh conditions: wet long winters, hot dry summers, poor soil nutrition and lots of wind. Fynbos has been around in the form of the Protea family since 60-70 million years ago, but most of the diversified fynbos we see today goes back to 6-8 million years.

In the same way that the soil at Cape Point is nutrient-poor for plant life, the plant life has passed on the favour to animals that need to feed on them. Fynbos is nutrient-poor also, and generally useless to most animals except for niche species and, to top it all, most fynbos is stockpiled with polyphenols that make them unpalatable and indigestible. Pollination is undertaken by ants, a number of types of insects, butterflies, mice and some birds such as the Cape Sugarbird, but one thing is common: they are all delicate partnerships. Not all plants rely on multiple pollinators and some serve only a few plants and, if this relationship was broken, the plants would cease to exist, such as the red disa uniflora and the mountain pride butterfly Aeropetes tulbaghia.

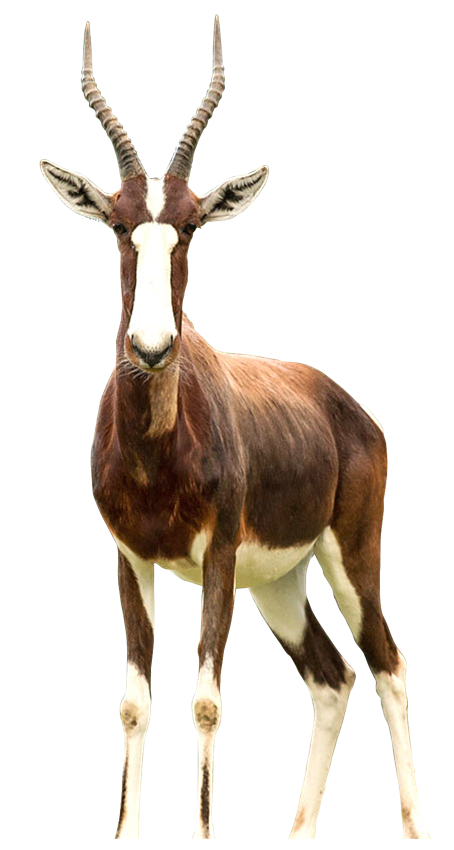

Today, we visit a national park expecting to see lots of animals but, in the case of Cape Point, it was never well-populated with animals and especially the big game that we come to expect from an African safari park. There was a time when big game visited this part of the world but, because of the lack of nutritional value of the vegetation, it would be safe to say these animals visited when they wanted to and then returned to greener pastures. The permanent animals, then and now, were generally smaller such as porcupine, klipspring, tortoise, dassie and the big attraction, the Chacma Baboon, of which, the first commander at the Cape, Jan van Riebeeck (1652-1662) said, “those big and horrible to look at...”. Some animals today have been reintroduced such as the ostriches which came from one of the origanal farms at the Point in 1865 and then there was the Bontebok which nearly went extinct in 1837 and, to safeguard its numbers, 12 were introduced into the Cape Point in 1960 (historically, this antelope was never found on the Cape Peninsula). There is a good chance of seeing the bigger herbivores as they get extra food on feeding lawns because of not getting enough nutrition from the natural habitat.

Was someone watching Dias?

Humans had made the Cape Point their home or temporary home for nearly 200 000 years. The evidence is there with over a hundred sites mainly middens (ancient rubbish dumps). One such site is just above Cape Maclear. These ancient people must have survived in small groups, living off small animals and whatever they could gain from the sea. There was a stage, 20 000 years ago, they would have had access to larger game when, at a Glacial Maximum, the Cape Point was surrounded by land. False Bay was dry land with over 20 km stretching out into the Atlantic Ocean, an ideal scenario for savanna game. There was also a time when the Cape Point was an island with a water channel running through the Fish Hoek Valley and sea surrounded the whole of Table Mountain; this happened 1,5 and 5 million years ago.

When Dias walked up to Cape Maclear to place his Stone Cross (some people think it might have been wood because no one has found it) he did not claim to have seen any local inhabitants. He knew they existed in this part of the world as, a few months earlier, he had encountered them at Mossel Bay. There is a possibility that Dias and party had been watched on this historic day but, with such small numbers, it might have been deemed too risky on the locals part for an encounter.

These local people over time would be named the Khoi (and also by many other names such as Khoi-na, Khoikhoi, Hottentot and Otentottu). The Khoi had migrated to the Cape some 2000 years ago from an area near present-day Botswana. They were predominately a cattle tribe with sheep and cattle but also could live off nature’s opportunities. The Khoi groups that lived around Cape Town had chosen areas where their cattle would flourish and the groups were large. The Khoi that were at the Cape Point were small and opportunistic, living off the land and sea; fish traps were constructed and whale and seal meat were consumed. Due to the nature of the Point, cattle were not a priority; also, these groups were loners and did not want to be discovered. There is no evidence that they were permanent but one thing is common, the Cape Point was a place for people who wanted to be away from the main stream of life and in small enough numbers not to be noticed. After Jan van Riebeeck made Cape Town a permanent settlement in 1652, the Cape Point also became an escape for run-away slaves and no-gooders such as tobacco thieves.

The first recorded encounter between the Cape Point Khoi and the Dutch was not a pretty episode. This was the first overland (spying) expedition to the Point in 1659 but ended at Noordhoek due to illness. The second expedition that same year was undertaken by Elias Giers who made it to the point where he encountered Khoi.He killed two, mortally wounded one who fell off the summit and also destroyed their camp. The rest of the Khoi retreated. Tension at the Cape, for a number of years, was running high as the Khoi considered their land stolen and the settlers considered theft from the farms, especially tobacco, unforgivable.

A highway to the East

The land at Cape Point, during the 1600 and early 1700s, had little value for the new settlers at the Cape, except for Simon van de Stel who claimed the whole of the Cape Peninsula beyond Groot Constantia as his cattle grazing right. There is no record of him ever using his self-given right but, we do know he personally visited Simonstown (named after himself) in 1687 but went no further. Simonstown was earmarked by him as a safe winter harbour which helped increase the flow of ships between the East and West which was growing exponentially. From Dias’s first rounding the Cape and the establishment of a refreshment station at Cape Town, the Portuguese, then the Dutch and French and, lastly, the British, exploited this new route.

Virtually all of the famous navigators of history have turned this corner at some point in time, from Bartolomeu Dias, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, Capt James Cook, Sir Francis Drake and Horatio Nelson. There was an increasing flow of ships, from the first small Portuguese caravels to the majestic, speedy clippers of the Cutty Sark fame which still used the Cape route (the Suez Canal had been opened in 1869 and was used by the early steamships which eventually killed the sailing ship business). These clippers were fast, for example the Cutty Sark set a record of 73 days from London to Sydney. There was once an organised race (1872) between the Cutty Sark and a steamship and, after setting a lead of 740 km, the rudder broke which was a great setback for the sailing ship, resulting in the steam ship winning by a week and the clipper doing the Cape Point route in 122 days.

The opening of the Suez Canal dented the flow of ships around the Cape Point for a time but, with the discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa and the two World Wars, the flow increased. With the advent of super-sized ships, there has been a swing back towards the Cape route as a result of the canal not being deep enough, piracy in the Red Sea area and, most importantly, with fuel prices down and canal tariffs being expensive, it was far cheaper to go around Cape Point even with an extra week of travel.

There was, however, a cost for rounding the Cape as many ships paid the price. As well as having some of the biggest seas in the world and extreme storms, stupidity and nefarious motives also played out in some of these disasters (Bartolomeu Dias, the founder of the route around the Cape Point, also became the first victim to the bad weather at the Cape in 1500).

One of the first ships to pay the price was the Colebrook in 1778 when it hit a partly submerged rock now known as the ‘Anvil’. She managed to make a run for a small bay on the other side of False Bay where she sank. The Third Officer rowed back in a small boat to Simonstown in ten hours to raise the alarm. The Rozette ran aground in 1786 and, a little while later, it was discovered under a bit of persuasive-torture , that the crew had murdered their officers for the treasure. Of the six, five died, torn limb from limb and beheaded, one was hanged and the last escaped with his life with ten years on Robben Island and banishment from the Cape. 1862 saw a boating disaster on a personal level at the point when the Rittman family, who lived at Buffels Bay, decided to relocate back to Simonstown. They decided to use a boat for their move and, on the way to their beloved bay, bad weather overturned their small boat drowning their child, sister-in-law and two sailors. In 1863, the Albatross went down on a submerged rock that later would take its name and most of the shipwrecks of the Cape Point. Thirty years later, this same rock sank the Kafir which was on its way to Zanzibar with Muslim pilgrims to Mecca; four Arabs died and were buried close by that same day (one of the Arabs who had died was once Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s bearer on the famous day when Stanley bumped into Dr Livingstone and the immortal words ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’were uttered.) but, besides the good fortune of being spotted by one of the farmer’s servants which ended with them being transported to Simonstown, all the survivors were arrested on the train to Cape Town for not having tickets. The first of the wartime victims was the S.S. Bia followed by the Liberty ship, the Thomas T Tucker in 1942 which was sailing in fog close to shore to avoid German U-Boats resulting in becoming another victim of the Albatross rock (36 German, Italian and Japanese U-boats operated off the South African coast, with a kill rate of about 4 per boat with a number of these off Cape Point.).

Enough about shipwrecks

With the number of shipwrecks growing, a lighthouse was started in 1859. The idea had been around since 1816 when land was granted to John Osmond on condition a lighthouse could be built on his new farm, Uiterste Hoek ‘further-most corner’. The lighthouse was designed by Alexander Gordon and pre-made of iron sections by Victoria Foundry, Greenwich to be assembled on site. The parts were transported from Simonstown to Buffels Bay by boat, then the parts were taken up to the top of Cape Point Peak on a converted gun carriage and then a sledge. Gordon, who had never visited the site, had recommended just placing it in position without bolting it down. He was convinced otherwise from people who knew the local conditions. The first lighthouse keeper was James Coe who had five kids in toe and his assistant who had three; all were schooled at Smitswinkel Bay. Water was supplied from Buffelsfontein farm once a week. It was not long before the maritime industry realised this lighthouse was not doing its job, not because of the distraction of all the kids but the location was not well thought out. In this part of the world, the fog can be very thick and hangs at a higher elevation that obscures the lighthouse, leaving a clear visible strip just above sea level. Also, it is not at the actual point and set back from the sea edge on all sides which created confusion among some captains.

The debate went on for years about building a lighthouse right on the edge of the point with most experts deciding it could not be done. What finally turned words into action was the tragedy of the Lusitania in 1911 where a Portuguese ship, carrying 800 passengers, hit the Bellows rock (4 km out to sea next to the Anvil); the ship went down with only eight deaths. Harold Cooper, a lighthouse engineer, convinced the nonbelievers and undertook this impossible task. He designed and supervised the whole project which started in 1913 and finished in 1919. The lighthouse was simple in design but it was the logistics of getting material to the site that was the challenge. He excavated a path on a near vertical cliff face with two tramways to get the job done (you can walk this route today on the Lighthouse Keeper’s Trail). Paraffin in vapour form was piped down from the old lighthouse until the lighthouse was electrified in 1936. Morse lamps were used to communicate with Simonstown before the first telephone was installed in 1881 and a permanent red light was installed to shine on the notorious Anvil and Bellows rocks. As much as the construction of this lighthouse was interesting, it must have been even more interesting for the lighthouse keepers perched on the end of the world and in conditions that can be some of the worst in the world. There was one story when the lighthouse keeper could not get the right mantle for his light, so he spent three days switching the light on and off by hand using a stop watch to emulate the lighthouse unique group flashes.

Visitors and farmers

By the end of 1700, the Khoi had gone from the Cape Point to be replaced by curious visitors and some people who liked living in isolation such as a coloured gentleman who went by the name of Pietersen who was clearing bush from Smitswinkel kloof. People found the isolation of the Point a great get-away for beach excursions and riding horses. As Simonstown grew and especially when the railway arrived there in 1890, more visitors arrived. One of the most interesting visits happened in 1824 when Lt James Holman of the Royal Navy was the first person to go to the very tip of Cape Point which was quite a feat for an able bodied man but, in this case, he was totally blind. Before some of these visitors, Jugen Schuster became the first farmer at the Point with his farm Wildschutsbrand in 1738. By 1786, three more families had taken up loan farms too - Jan Willem Hurter at Olifantsbos, Arend Munnik at Schuster’s Kraal and Jeremias Auret at Buffelsfontein. It was only after the British had taken control of the Cape in 1795/1806, that more farmers established themselves at the Point because of a new lease agreement (1813) whereby the descendants of the farmer could become the lease holders in ‘perpetual quitrent’. This inviting deal saw many more farmers come to the Cape Point, the first being John Osmond (Buffelsfontein and Uiterstehoek) and, by 1816-17, eleven new land grants were handed out, including Petrus Hugo (Smitswinkel), Frans Daniel Roussouw (Olifantsbos), Gerhardus Hurter (between Olifantsbos and the Krom River) and, as time went on, more names were added such as John McKellar who bought John Osmond’s concern. George Smith bought the farm from McKellar in 1886 where it became known as Smiths Farm where many a visitor enjoyed his refreshments and accommodation (public had access rights to the beachs and Sirkelsvlei). One thing which was common with these farmers was the poor farming soil was not going to sustain their livelihood and they were very far from the market place in Cape Town with access challenges over Red Hill. So, diversifying into lime-making, treknet fishing, ostrich farming, a hospitality industry to visitors and whaling at Buffels Bay were all needed to sustain living in this part of the world.

The vision in 1915 of Sir Frederic de Waal (administrator of the Cape Province) to build a road route right around the Cape Peninsula and the hard work of George Boyes opened up the south-western tip of Africa even more. With the road now open from Simonstown to Smitswinkel and a train line from Cape Town to Simonstown, the property developers started taking note.

‘Not enough grass to keep a scorpion alive’

By the beginning of the 1900s, the properties and farms that made up the Cape Point were used more for recreation then farming and with all the new visitors, the property developers could see the potential for making big money. Some Capetonians, who saw the inevitable, decided the only way to stop the pillage of their sanctuary, the last unspoilt area on the Cape Peninsula, was to push for this area to become a nature reserve. Dr S.H. ‘Stacey’ Skaife (naturalist, author and broadcaster) and Brian Mansergh (architect) led the charge with other players and property holders of the Cape Point, namely the Smiths of Smith’s Farm which they wanted to sell but not to a developer at all costs. The Smiths land would be the pivotal land for a park to work. On numerous occasions, the Cape Town City Council was approached for finance and help but they did not see the value in this venture, as illustrated by Councillor A.Z. Burman who stated at a public meeting, that there was ‘not enough grass to keep a scorpion alive’. Skaife, in reply, stated that he was not qualified to speak on the subject as scorpions don’t eat grass. A Cape Point Preservation Society was established in 1938 and, by the following year, a vote was taken at a public meeting where the majority wanted the nature reserve. The City Council were unmoved, much to the relief of the Cape Divisional Council who saw the bigger picture of a reserve. They put up the money for the Smiths farm and started buying up the other farms ending with the first farm established at the Cape Point, Wildschutsbrand. The Hare family contributed most of their land and the Smiths sold their land at a vastly reduced price in order for the reserve to happen. There were many other individuals who put in a lot of work to make this happen and their silent reward is an unspoilt piece of land at the end of the Cape Peninsula. By 1938, the park was declared and named The Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve (the economical name ‘Cape Point’ is widely used today even though it is not the offical name). The naming of the park was put out for public input, with names such as Dias Park, Vasco da Gama Park to the slightly unusual, like Umbrella Park and then to top it all Pixie Point, Elf Land and Sea-Girt Zoo, as some of the suggestions. In 1998, the Cape of Good Hope was incorporated into the Table Mountain National Park and renamed as such in 2004.

Military manoeuvres

The celebrations of the new park were short lived as, nine weeks later, the world went to war. Knowing that Cape Point was one of the most important shipping lanes in the world, numerous listing posts, observation posts, signal stations and radar stations were installed, some dating back before the First World War. On one WWII military manoeuvre, an old cannon was found dating back to the Dutch period on Kanonkop. During 1914-1918, a unit of the Cape Mounted Rifles was permanently based at the Point. During the two World Wars, manoeuvres and gunnery practice took place, leaving many craters that can still be seen today. 1939 saw Klaasjagers as a permanent training camp. One of the most important military installations at the Cape Point was the first radar station in South Africa which, for its time, was equal if not ahead of Europe’s radar programmes. Basil Schonland, a professor of geophysics at the University of the Witwatersrand (now considered one of the greats in radar technology), designed and built homegrown units to be placed on the South African coast, starting with Cape Point in 1941. The station at Cape Point was first manned by men but was replaced by women as they did a more efficient job. The knowledge of a radar station at the Point by the enemy was effective in deterring enemy submarines coming too close to land but, in reality, no submarines were ever picked up on radar at the Point.

From Titans to ghostly ships

Who would have thought that Greek mythology is found right here at the Cape Point? It all started before the Greek Gods such as Zeus, Hades and Demeter. The earth and the sky gave birth to twelve Titans who, for a matter of sport, unleashed havoc upon the earth. Cronos and his wife had children, who became the Greek Gods who eventually turned on their parents, defeated them and banished most of the Titans to an underground prison. Atlas was sent to North Africa, where he would hold up the sky on his shoulders, Helios had to drive the chariot that pulled the sun around the earth and Adamastor was turned into a jagged mountain at the southernmost tip of Africa, in other words, the Cape Peninsula and namely the Cape Point. So, to this day, the violent storms at the Point that have wreaked havoc on shipping over the last 500 years are the anger of a banished Titan.

The most famous legendary ghost ship in the world has is roots at the Cape Point, from Wagner’s opera ‘Der Fliegende Hollander’ to the Walt Disney film ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’, this story has been retold, embellished and relocated all over the world since 1641. For some people at the Cape, this was not just a story, with numerous official sightings, first recorded at Danger Point at Gansbaai, by the Royal Navy on a number of occasions, a German U-boat, lighthouse keepers at Cape Point and landbase sightings off Muizenberg and Glen Cairn beach. The tale of The Flying Dutchman has many variations but one is of Captain Hendrick van der Decken (the Dutchman) whose vessel sank in 1641 on a return journey from the East when he hit a violent storm off Cape Point. On account of the ship being destroyed and sinking, the crew begged the Captain to turn back. The Captain refused whereby he challenged the wrath of God Almighty by swearing a blasphemous oath. The crew mutinied, Decken killed the rebel leader and threw his body into the sea. As the rebel’s body hit the water, the vessel spoke to the Captain “asking him if he did not mean to go into the bay that night”. Van der Decken replied: ‘May I be eternally damned if I do, though I should beat about here till the day of judgment’”. The ship spoke again, “As a result of your actions, you are condemned to sail the oceans for eternity with a ghostly crew of dead men bringing death to all who sight your spectral ship and to never make port or know a moment’s peace. Furthermore, gall shall be your drink and red hot iron your meat.” At this, Captain van der Decken did not quaver for an instant. Instead he merely cried “Amen to that!”. Since then, Captain van der Decken has been given the name the Flying Dutchman, sailing his ghost ship the world over. Sailors claim the Dutchmen has led ships astray, causing them to crash on rocks or reefs. They say that if you look into a fierce storm off the Cape of Good Hope, you will see the Captain and his skeletal crew. But beware, legend has it that whoever catches sight of the Dutchman will most certainly die a gruesome death.

There is a safer Flying Dutchman that you can catch sight of today without dire consequences and you can even get to ride it to the top of Cape Point peak. The Flying Dutchman funicular was the first commercial funicular of its kind in Africa and has ferried millions of visitors up to the old lighthouse. For those who do not want to pay for this service, the pleasant walk up, with its numerous viewing platforms, is just as rewarding. Enjoy the views from one of the four great Capes in the world. Visit the rest of the reserve and discover its secrets and solitary places. Who knows, maybe you might be lucky to see something unusual like the ice berg that was spotted off the Cape of Good Hope in 1850?

The tranquil Bordjiesdrif picnic spot and tidal pool with False Bay and Kogelberg in the background.

Dias Monument was built to commemorate the 1488 rounding of the Cape which doubles up as a navigational positioning beacon. On viewing the monument, you will note that the two sea-facing sides are painted black - this is to make it more visible against the skyline.

World War Two military blockhouses (radar outpost) on the Lighthouse Keeper’s Trail.

Looking down from below the old lighthouse on Cape Point Peak towards Cape Maclear and the Cape of Good Hope (beyond), the South-Western-most point in Africa.

Harold Cooper’s, Cape Point lighthouse built in 1919 to replace the earlier 1860 lighthouse built on top of Cape Point Peak.

Viewing sites on Cape Point Peak.

Platboom Dunes

Buffels Bay has been home to many peoples for thousands of years.

South-Westernmost point in Africa, Cape of Good Hope with Cape Maclear on the left.

The Flying Dutchman. Illustration by Gregory Robinson for Rudyard Kipling’s poem Seven Seas.

Da Gama Monument erected by the Portuguese government to commemorate his voyage and to double up as a navigation beacon; when lined up with the Dias Cross, they point to Whittle Rock in False Bay, a shipping hazard.

Restored Old Lime Kiln built around 1890 near Boot se Skerm where travertine was made by utilising the surrounding calcareous rocky outcrops in this area.

The Origins of Early Southern Sapiens Behaviour exhibition is found at the Buffelsfontein Visitors Centre. The exhibition showcases remarkable discoveries from SapienCE main excavation sites augmented by Sea Change Project contribution.

A view from Platboom.

Lighthouses of the Cape Point

Cape Point (Original)

This lighthouse, which was commissioned in 1860, stands 8m high and is a circular prefabricated cast-iron structure. It is located at 262m above sea level. The lighthouse had one flash every 12 seconds, with a 32-nautical-mile range. When the new Cape Point light house was built, the old lighthouse became a watch room and communication monitoring centre.

Cape Point (Present)

This lighthouse was built to replace the original lighthouse due to its location flaws. The new 9m high square masonry lighthouse with a white lantern house was commissioned in 1919 and built 87m above sea level on Diaz Point. The light as a composite group flashes 3 times every 30 seconds. The light has a 63-nautical-mile range, making it the brightest light on the South African coast at 10-million candelas.

Geology of the Cape Point

The Cape Peninsula, of which the Cape Point is a part, was formed 560 million years ago at the bottom of the extremely ancient Adamastor Ocean (Proto-Atlantic Ocean). After millions of years of this ocean filling up with silts sediments, which were then folded and then eroded, three rock-formations remain visible (like layers of a cake). Twenty million years later, after the first sedimentary formation was put down, molten magma intruded this formation, cooled down over millions of years to become crystallized as granite and later exposed to the surface due to erosion. This Granite Suite underlies most of the Cape Peninsula. Above this granite, two more sedimentry formations were laid down. The last rock type to be seen in the Cape Point is very young surface deposits of aeolianites (dune-rocks).

Visible rock formations at Cape Point

Not all the rock formation that make up the Cape Point are visible. The Cape Granite Suite can be seen at the very tip of Cape Point and on the left hand corner of Smitswinkel Bay but, due to the Smitswinkel fault, all the rock formations within the reserve have shifted downward, placing the granite below sea level, leaving only the Graafwater, Peninsula and Langebaan Formation visible.

The Table Mountain Group’s Peninsula Formation

The youngest of the sedimentary formations (490-410 million years) which make up the bulk of the Cape Peninsula is a very hard, thick-bedded, quartz-rich sandstone. This was formed in deep, fast southward-flowing rivers.

The Table Mountain Group’s Graafwater Formation

Visible just above the Cape Granite at the tip of Cape Point and beside Dias Beach. These mudstones and quartz sandstones

were deposited mainly by southward-flowing rivers, about 490 million years ago. During dry seasons, the floodplain muds were exposed to oxygen in the air thus causing a maroon colour.

The False Bay Dolerite Dyke Swarm

This black igneous rock, which is 130-million-years old, has intruded the older rocks when the Supercontinent Gondwana broke up. These dykes, with magnetic material, have helped map continental drift. Examples are found at Smitswinkel Bay and Dias Beach.

The Sandveld Group’s Langebaan Formation

The youngest rock type is aeolianites (dune-rocks, sand grains of quartz and shell fragments, cemented with calcite) which were deposited, about 200 000 years ago, by summer southeasterly winds. These limestones can be seen at Bordjiesdrif and Dias Beach.

Wildlife of the Cape Point

Cape Mountain Zebra

Bontebok were nearly relegated to history in 1837 when there were only 27 Bontebok left on the planet.

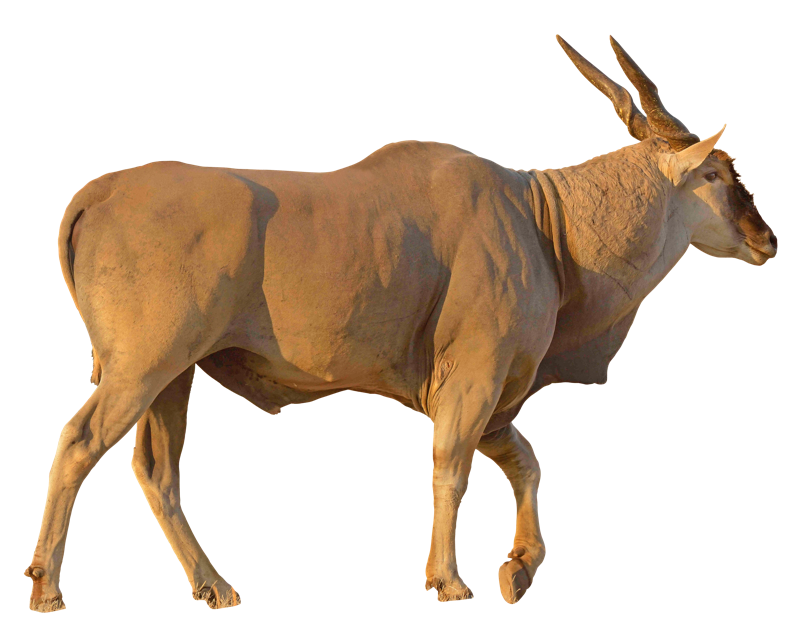

The Common Eland is the 2nd largest antelope in the world after the Giant Eland

Chacma Baboon of the Cape Point, the most southerly primate in the world, is one of ±11 troops on the Cape Peninsula and is the only protected population of the

species in the world

Klipspringer (which means “rock jumper” in the Afrikaans language) is one of the 10 smallest antelopes in South Africa

Angulate tortoise are the

only tortoises in Africa with

a single throat shield (angulata).

The dassie or Cape hyrax is the only living species in the genus Procavia; its closest living relative is the elephant.

For More Information

Tourist Information

www.capepoint.co.za www.baboonmatters.org.za

www.sanparks.org

Editing:

Shelley Brown and Shelley Woode-Smith

Thanks to Dr John Rogers for geological input.

© Richard Smith • Gateway Guides • 2023

Distribution: GoSeeDo • Printing: FA Print

The flightless ostrich is the largest bird in the world and is the fastest running bird at 70 km.

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

© Richard Smith

Citations available on request.