Lion’s Head (Leeukop) Spiral Path 670 metres • Trig Beacon 51

...for a memorial hereafter we have made a heap of stones on a hill lying west-south-west from the road in the said bay, and call it by the name ‘King James His Mount’.

English Naval Officers, Humphrey Fitzherbert and Andrew Shillinge, issued a proclamation annexing Table Bay in the name of King James I.

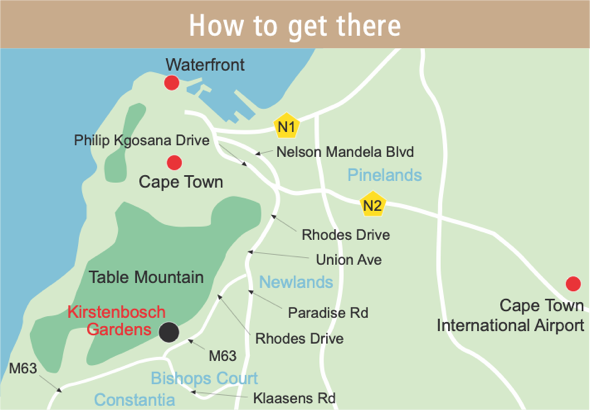

The start of the Spiral Route up Lion’s Head. Remember to bring a tip for the car guard.

Lion’s Head

Lion’s Head, at 670 m, is not the highest of the many peaks that make up the Cape Peninsula mountain chain, but it is a mountain in its own right (a mountain is defined as ‘any peak that is over 305 m above the surrounding terrain’) and an important landmark as it is one of the three iconic peaks that frame the city of Cape Town. In addition, Lion’s Head stands head and shoulders above all its neighbours when one takes into consideration the number of people who climb it. It has been estimated that over 200 000 people a year reach its summit, making it the most-climbed peak in South Africa. Many Capetonians have walked up Lion’s Head at least once in their lives, whether during the day or for the popular full-moon pilgrimage, when (along with crowds of other people) one can enjoy a picnic while watching the sun set and the full moon rise before descending by torchlight.

What makes the walk up Lion’s Head so popular,we might ask? One answer is its convenience with regard to time: from the city, its slopes can be reached within ten minutes, and the summit can be reached within an hour of leaving the car park. Other important factors are that it offers breathtaking 360° views of Cape Town (one of the top ten tourist destinations in the world), has Table Mountain (one of the recently proclaimed seven natural wonders of the world) as its backdrop, and is situated in one of the smallest but richest floral kingdoms in the world.

This route should not really be described as just a ‘walk’, for it involves some interesting additional aspects: ladders, a chain traverse, an exposed summit-ridge scramble and the famous chain ladder that has just recently been upgraded to steel handles for safety reasons.There are other walking routes to the summit, but they involve serious scrambling with exposure and these routes have to use the normal summit ridge as well, shared with the standard Spiral Path route. There are numerous rock climbs to the summit but these should only be undertaken by experienced rock climbers or with a qualified guide. This Gateway guide will cover the standard ‘Spiral Path’ which, in its own right, is one of the most exciting walks in the Cape Peninsula.

Before we get into the description of the walk, there are layers of the geological story that need to be told to give you a fuller picture of this peak and to enrich your experience. The story of Lion’s Head is shared with the rest of the Peninsula mountain chain.

A geological marvel

Lion’s Head is one of the few places in the world where you can walk past three different rock units and view, down by the ocean shore, a fourth one that Charles Darwin visited in 1836, on his famous journey around the world in the HMS Beagle.

The different rock units that you encounter on the walk up Lion’s Head today are due to the changing geological environments which altered the nature of the rock type. The story starts about 560 million years ago with the extremely ancient Adamastor Ocean, in which silt was deposited (18km thick), that became the siltstones of the Malmesbury Group, the foundation for all the rock units that we see today on Lion’s Head. These dark grey siltstones can be viewed from Lion’s Head when you look down at the Sea Point promenade. This stone fractures easily: on close inspection, you can see unspoilt lamination from being deposited in a lifeless, oxygenless ocean.

About 540 million years ago, the Malmesbury Group was intruded by molten magma of the Cape Granite, which forced its way into the siltstones and cooled slowly to form a granite pluton (50 km in diameter) 10 km underground. The contact zone between the massive hot magma and the country rock (in Cape Town, the Malmesbury Group) was a focal point of Darwin’s stopover in 1836. These two different types of rock did not just sit side by side when the hot magma intruded. Folding occurred in the Malmesbury siltstone so once-horizontal beds were pushed up to become nearly vertical. The siltstone that was closest to the heat was metamorphosed, forming a tough baked rock called hornfels (‘fels’ meaning ‘rock’ in German), which is very dark grey in colour. The intrusion of granite marked the turning point in the history of Lion’s Head as, for the first time, instead of subsidence taking place, everything started to uplift.

There was a gap of about 20 million years before the sediments of the Table Mountain Group were laid down during the time of the supercontinent Gondwana. The base of the Table Mountain Group on Lion’s Head is a 60 m layer of mudstone and sandstone called the Graafwater Formation, sitting on the uplifted and eroded top of the Cape Granite. The maroon colour of the mudstone is proof that the original mud was exposed to the air, causing oxidisation. This layer was probably made in a quiet estuarine or tidal mud flat. Sand of the younger (400-500 million years) Peninsula Formation was probably deposited in river channels, as the grains were large enough to settle in faster-flowing water. It must be remembered that it took millions of years and great pressure for these sediments to form cemented rock.

Walking through the Silver Tree forest at the end of the jeep track just after the paragliding launch site.

There were at least five more rock formations above Lion’s Head which have been eroded away. These formations must have applied great pressure in terms of sheer weight to form the hard Peninsula Formation sandstone we see today, which extends to the top of Lion’s Head. It consists of light grey sandstone with 98% quartz (silicon and oxygen – SiO2) with tiny amounts of iron, manganese and other elements.

This formation was deposited by rivers in a sinking basin to a thickness of at least 1200 m. Over time, most of the mountain has eroded away, leaving the bullet-hard sandstone which creates very steep terrain with vertical cliffs and overhangs.Along the Lion’s Rump and Signal Hill, which is made up of Malmesbury siltstone, this section has a rounded appearance as siltstone is a softer rock which erodes much more quickly. All these rock units are hundreds of millions of years old: if you are looking for fossils, you will be disappointed as there were only very primitive organisms lacking hard bodies at this time. If you are looking for something more interesting like trilobites and brachiopods, you will have to visit the Cederberg. The Cederberg Shale Formation, which once covered the present-day summit of Table Mountain, has since been eroded away.

The lion’s share of the floral kingdom

Lion’s Head is situated within the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest Floral Kingdom in the world (0.04% of the world’s land surface area) but the richest in terms of species, as it boasts over 9000, of which two thirds are endemic to the Cape. The floral wealth of this area was recognised by the English naturalistWilliam Burchell, who, after visiting Lion’s Head in 1810, compared what he saw to a “botanic garden, neglected and left to grow into a state of nature; so great was the variety everywhere to be met with”.

A lot of the plant life around you as you walk up Lion’s Head is of a vegetation type known as fynbos. Perhaps the best-known example of fynbos is the King Protea, the national flower of South Africa. The pride of Lion’s Head, however, is probably the Silver Tree, the tallest species in the Protea family. Its name derives from its silver leaves which shimmer in the sun (the silvery sheen is thought to protect the tree from heat by reflecting sunlight.) On your walk up from the car park, you will see groves on both sides of the path.These trees are on the endangered list and have, at times, come close to being lost. One of the things that has nearly destroyed the Silver Tree is also what preserves it:fire.Like all fynbos,these plants need fire at the right time and right temperature for the seeds to germinate. If fire occurs too frequently or infrequently, the plants will die. However, the groves on Lion’s Head have managed to flourish in the last few years and groves on Devil’s Peak and Vlakkenberg have been cultivated, so the risk of extinction has diminished. On Signal Hill another vegetation type, Renosterveld, can also be seen.

Here be lions

Thousands of years before humankind set eyes on it, Lion’s Head was the domain of animals. From the first written records by visitors to the Cape and the early European settlers, we know that all the big animals like elephants, hippos, lions, hyenas and leopards were present around Cape Town in the late 1600s. The records also tell us that the last wild lion on Lion’s Head was shot in 1802 and the last leopard in the 1820s. Caracal, and the extremely rareAfrican wild cat, have managed to survive. Today, besides the rock agama, black girdled lizard, dassies and porcupines, not much else can be seen. Hopefully one day the national parks will introduce the elusive little klipspringer that once roamed these slopes.

The arrival of people

The first people to set eyes on Lion’s Head, and more than likely climb its summit, were the Stone Age people who had made the Cape Peninsula their home, followed by the San and later the Khoi-Khoi, who were around more than 2000 years before the first Europeans.A sketch of Table Bay by Peter Kolbe (first astronomer at the Cape from 1705-1713) shows two large Khoi-Khoi kraals situated on the slopes of

Lion’s Head.

The first written records began with the coming of the Europeans. Bartholomeu Dias recorded seeing Table Mountain, as well as Lion’s Head, in 1488. We do not know who the first European man to climb Lion’s Head was, but it is recorded that in 1682 the wife of Ryklof van Goens (the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies) climbed it with Simon van der Stel, Governor of the Cape.

To commemorate the event, a two- metre-high brick pyramid was erected, but this has long since disappeared. In the true spirit of colonisation, Lion’s Head would be claimed, named, mapped, probed, dug into and built upon.The first to leave their mark were the Portuguese; instead of erecting their traditional stone cross on the summit, they hacked a large cross-shaped fissure into a rockface near the summit.This cross can still be seen today, but most believe it is natural and the story is but a legend.

What’s in a name?

Disregarding any local name given to these places, the English, on 3 July 1620, supplied their own names for Lion’s Head and Signal Hill. The background to this naming is quite interesting: it was part of a show of pretence to keep the Dutch from thinking they could occupy Table Baywithout the English putting up some form of resistance.Two high-ranking

English naval officers, Humphrey Fitzherbert and Andrew Shillinge, issued a proclamation annexing Table Bay in the name of King James I, and stating “... and for a memorial hereafter we have made a heap of stones on a hill lying west-south-west from the road in the said bay, and call it by the name ‘King James His Mount’ “.Thus Lion’s Head was briefly known as “King James Mount” while Signal Hill was named “Ye Sugar Loaf”. The annexation by the English was never confirmed and the Dutch subsequently took control of Table Bay and the Cape, providing the names “Leeuwen Kop” (Lion’s Head) and “Leeuwen Staart” (Lion’s Tail), which later became Signal Hill.

Signals from the summit

The first official use of Lion’s Head was in 1673 when a permanent watch station was placed on the summit. This station was manned by up to three men with a small signal cannon and a flag. The cannon would be fired whenever a ship was spotted, thus informing the castle down below. By the early 1700s, a hut had been built on Kloof Nek, then known as Vlaggeman’s Kloof (Flagman’s Ravine), for the use of those who manned the station.

When the old mud fort of Van Riebeeck was to be replaced by the Castle of Good Hope, Signal Hill was one of the proposed sites. As we know, the fort did not move to Signal Hill, but part of Signal Hill moved to the Castle in the form of stone cut for its foundation.

Under British occupation, a signalling station was built on Signal Hill in 1815, replacing the old Dutch cannon on the top of Lion’s Head.The old method of cannon fire as a signal was also replaced with a new system of a series of variously shaped flags, accompanied by a varying number of balls hoisted to the top of a flagstaff, indicating what kind of ship had been seen and where it was from.

In 1902, once again a cannon was hauled up the mountain, but this time to a lower position on Signal Hill. This large cannon gave the ships in the bay accurate time for setting their chronometers for navigational purposes; in addition, the people of Cape Town set their watches by it. The cue for the cannon to be fired was sent via a flare shot off at the Royal Observatory in Mowbray; this ritual of firing a cannon for time-keeping had started at the Castle in 1833. Today, at 12 midday, you will still hear the Noon Gun, as it is now called, booming across the city from the slopes of Signal Hill. This is the oldest continuing tradition in Cape Town and two of the oldest working cannons in the world are still used.

A place to live, die and be buried

Cape Town was virtually built on slavery like all colonial outposts. It is estimated that in 1834 there were over 35 000 slaves in the Cape. As Cape Town expanded, a small community of ex-slaves, artisans, political exiles (scholars and religious leaders) and people of mixed parentage established a home on the slopes of Signal Hill in an area which was known as the Malay Quarter, now home mainly to the descendants of the original inhabitants. (The word ‘Malay’ was used as a blanket term for

anyone who came from the East, especially the Indonesian archipelagos.) Now known as the Bo-Kaap, with its interesting streets, traditions and unique culture, the area is well worth a visit. One of the Bo-Kaap’s biggest influences was the establishment of the Islamic faith on the southern tip of Africa by one of its own, known as Tuan Guru, who is buried in the Bo-Kaap. (Islam was first introduced to the Cape at a farm in Constantia by Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah in 1668.)

The Bo-Kaap is also home to the oldest mosque in the country, the Auwal mosque (1798).

Relax with friends or family and enjoy a great picnic.

A panoramic view of the Garden showing the Main Pond (centre left) and the Cape Fold Mountains in the distance.

From Gate 2, there is an impressive approach to the Garden, into which one is led through paved open spaces and stone steps forming an amphitheatre.

Some of the Flora & Fauna found in the Garden

King Protea Protea family

This is South Africa’s national flower. It is the largest Protea in the Protea family and is also known as the ‘king’ of the Cape Floral Kingdom.

King Proteas grow wild in the mountains of the Western and Eastern Cape.

Silver Tree Protea family

These trees, with their silky silver leaves, are

unique to the Cape Peninsula. The wild

population is half what it was 60 years ago.

They are rare and endangered. You can see them in the Peninsula Garden, the Fynbos Walk and Silvertree Trail.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Alice Notten, SANBI

Pincushion Protea family

There are 52 species of pincushion, most of which are found in the Western Cape. They make a rewarding garden plant. They can be

seen along the Fynbos Walk and in the Protea, Restio, Erica and Waterwise Gardens.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Whorled Heath Heath family

This species of Erica used to grow wild in the area between Rondebosch and Rondevlei but the spread of Cape Town’s suburbs caused it to die out by the early 1900s. It was saved from extinction and now can be seen in the Garden of Extinction and Erica Garden flowering between November and February.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Albertina Thatching Reed

Restio family

The stems of this species are used for thatching roofs in the Cape tradition. Restios, reed-like perennials, show a great diversity of form. Some are as small and light as grasses and others resemble bamboo. See them in the Restio Garden, Fynbos Walk and the Useful Plants Garden.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Wild Almond Protea family

It grows wild at Kirstenbosch and is famous for being the species used by Jan van Riebeeck for his hedge in 1660. See these trees at Van Riebeeck’s Hedge, at the top of the Concert Lawn and edge of the Arboretum.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Red Disa Pride of Table Mountain Orchid family

This is the emblem of the Western Cape and is endemic to this region. Disas can be seen in flower in the Conservatory Bulb House from February to March. In the wild, they are found near streams and on mossy cliffs.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Krantz Aloe Asphodel family

This From May through July, the Krantz Aloe bears flowers of bright orange or yellow. Aloes and many other succulent plants can be seen in the Conservatory, Vygie garden, Mathews Rockery and the Koppie.

Alice Notten, SANBI

White Namaqualand Daisy Daisy family

Spring is when the Namaqualand daisies put on their annual show of colour. In addition to white, these daisies come in shades of peach, yellow, blue, orange, mauve and purple. See them in the Annual Beds, Peninsula Garden and on the Koppie.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Wood’s Cycad Cycad family

This species is extinct in the wild; only 500

survive in botanical gardens and nurseries

around the world. It can be found in the Cycad Garden just above The Dell. Its base is protected from Cycad thieves by a metal cage.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Lesser Double-collared Sunbird

These small, brightly coloured birds are natural to Kirstenbosch and visit proteas, pincushions, aloes, tube-flowered heaths and similar plants to

feed on nectar. The Orange-breasted Sunbird, with its purple collar, and the green Malachite Sunbird, can also be seen in the garden.

Alice Notten, SANBI

The Helmeted Guineafowl

These are common in Africa south of the Sahara, but strangely did not appear in the Western Cape prior to 1900. They can invade picnics and become quite aggressive during breeding season. Stay clear and do not feed them.

Alice Notten, SANBI

Caracal (rooikat • African Lynx)

This is a medium-sized wild cat native to Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, Pakistan and northwestern India. It weighs about 8–19 kg and can reach a height of 40–50 cm at the shoulder.

At one time, it was rare to see one on Table Mountain but, with the introduction of the Urban Caracal Project, a lot more have been sighted.

Alice Notten, SANBI

For more information

www.sanbi.org (click on Kirstenbosch)

Join the Kirstenbosch family

Become a member of the Botanical Society of SouthAfrica

Tel: 021 797 2090 • info@botanicalsociety.org.za

Editing: Shelley Brown and Shelley Woode-Smith

Thanks to Alice Notten for photographs and information

© Richard Smith • 9th edition, 2023 • Gateway Guides

Richard Smith

083 260 2985

richard@gatewayguides.co.za

richardsmith.redzone@gmail.com

www.gatewayguides.co.za

www.historicaltimelines.co.za

© Richard Smith • Gateway Guides • 2023

Distribution: GoSeeDo • Printing: FA Print

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

© Richard Smith

Citations available on request.